When a patient gets a biosimilar drug like Inflectra or Renflexis instead of the original Remicade, the billing process isn’t as simple as handing over a generic pill. Unlike traditional generics, biosimilars are complex biological products, and how they’re paid for under Medicare Part B has its own rules, codes, and quirks that even experienced billing staff can struggle with. If you’re a provider, pharmacist, or just trying to understand why your bill looks different, here’s how it actually works - no jargon, just the facts.

How Biosimilars Are Coded Differently Than Generics

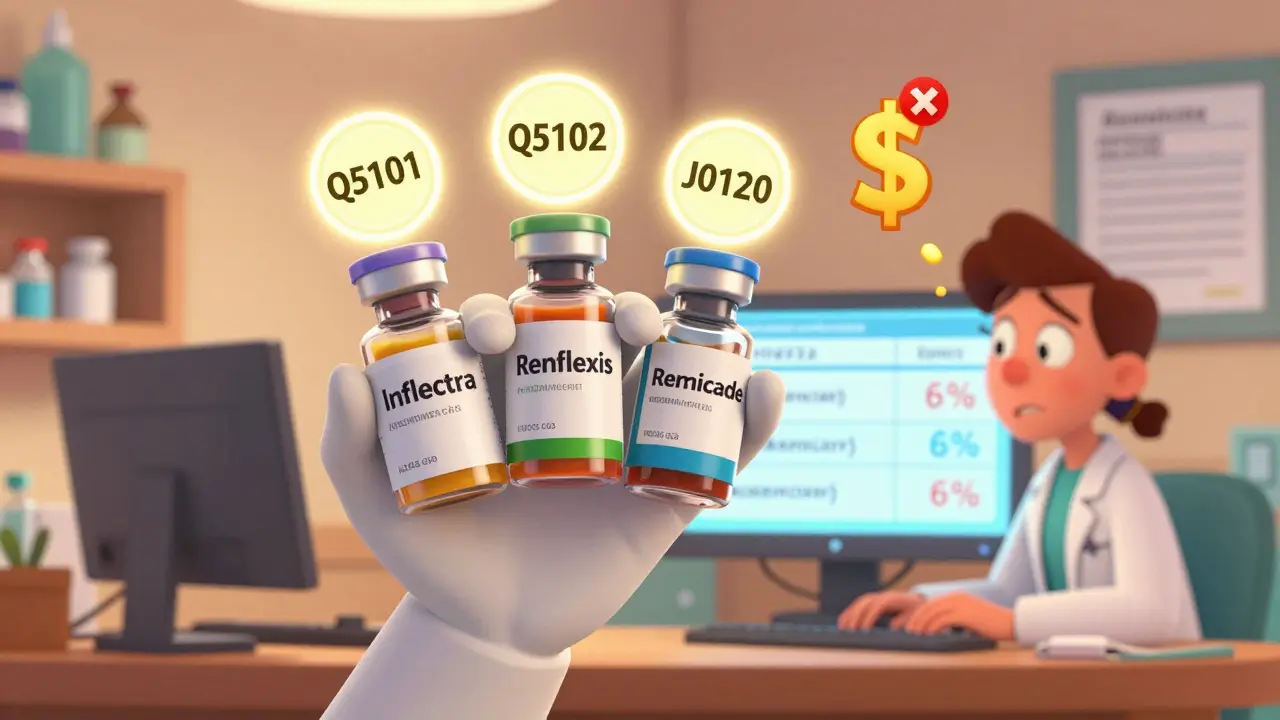

Most people think all cheap versions of drugs are the same. But biosimilars aren’t like aspirin generics. They’re made from living cells, not chemicals, and each one has its own unique identity in the billing system. In 2018, Medicare switched from using one shared code for all biosimilars of a drug (like infliximab) to giving each biosimilar its own HCPCS code. That means Inflectra, Renflexis, and Avsola each have their own code - Q5101, Q5102, Q5103 - instead of all being lumped together. This change was made because when they used one code, manufacturers had no incentive to lower prices. If one biosimilar came in cheaper, the payment didn’t drop - it stayed based on the average of all products. Now, each one gets paid based on its own Average Selling Price (ASP), which pushes competition and lowers costs over time.The 106% Reimbursement Rule - And Why It Matters

Medicare Part B pays providers 106% of the ASP for every biological drug, whether it’s the original or a biosimilar. That 6% is supposed to cover handling, storage, and administration costs. But here’s the catch: for biosimilars, that 6% is calculated based on the reference product’s ASP, not the biosimilar’s. So if Remicade costs $2,500 per dose and Inflectra costs $2,000, the provider gets $150 in add-on payment for Remicade ($2,500 × 6%) but only $120 for Inflectra ($2,000 × 6%). That $30 difference per dose adds up fast. A clinic giving 100 doses a month could be losing $3,000 in revenue just by switching to the biosimilar - even though the drug itself is cheaper. This creates a financial disincentive for providers to use biosimilars, even when they’re safe and effective.The JZ Modifier - A New Layer of Complexity

Starting July 1, 2023, Medicare added a new rule for infliximab and its biosimilars: providers must use the JZ modifier on claims when no drug is discarded. That means if you draw up a full vial and use every last drop, you mark the claim with JZ. If you have leftover drug - say, you’re treating a 70kg patient and the vial is meant for 100kg - you don’t use the modifier. This sounds simple, but it’s caused major headaches. A 2023 survey of gastroenterology clinics found that 30% of billing staff spent significantly more time just verifying discard amounts. The modifier was introduced to prevent overbilling, but it’s added paperwork without changing the actual payment. Providers now need to track vial sizes, patient weights, and discard logs - all just to get paid correctly.

Why Providers Still Use the Original Biologic

Despite lower prices, biosimilars haven’t taken over the market. In the U.S., infliximab biosimilars have only reached about 35% market share five years after launch. In Europe, that number is 75-80%. Why the gap? It’s not about safety - all FDA-approved biosimilars are proven equivalent. It’s about money. A 2022 survey of 217 cancer centers found that providers continued to use the reference product for high-revenue drugs because the reimbursement structure didn’t reward switching. Even when a biosimilar was 20% cheaper, the provider’s profit margin didn’t improve enough to justify the administrative hassle. Some clinics even kept using the original drug simply because their billing software hadn’t been updated to handle the new codes.What Happens When a New Biosimilar Enters the Market

When a new biosimilar launches, it doesn’t immediately get paid at 106% of its ASP. For the first six months, CMS uses the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) instead. This gives manufacturers a grace period while they build up enough sales data to calculate a real ASP. After that, the payment shifts to 106% of the actual ASP. But here’s the twist: once the first biosimilar is in the market, any new entrant skips the WAC phase. They go straight to the payment system based on their own ASP. This encourages early adopters but doesn’t help latecomers catch up. A biosimilar that launches six months after the first one gets no advantage - even if it’s priced 30% lower.

How Providers Get It Right - And What Goes Wrong

Successful practices have two rules: verify the code and cross-check the product. Many claim denials happen because someone used an old HCPCS code or picked the wrong one. Fresenius Kabi’s 2023 coding guide showed that 22% of initial denials were due to outdated codes. The best clinics now use dual verification: a pharmacist checks the vial before administration, and the billing team confirms the code matches before submission. This cuts error rates from 12-15% down to under 3%. Training matters too - during the 2018 transition, clinics that spent 40-60 hours training staff saw far fewer issues than those that didn’t. CMS provides official updates quarterly, but providers say it’s too technical. Many rely on manufacturer guides instead - and 87% of those surveyed found them helpful.The Big Picture: Why This System Is Holding Back Savings

The U.S. biosimilar market hit $12.3 billion in 2022, but that’s still only 18% of the total biologics market. Europe spends far less on these drugs because their reimbursement systems use reference pricing - meaning all products in a class are paid the same amount, and the lowest price wins. That forces competition. In the U.S., the current system keeps the reference product’s ASP tied to biosimilar payments. Experts like Dr. Mark Trusheim of MIT argue this creates a perverse incentive: providers earn more per dose from the more expensive drug. Studies suggest that if the 6% add-on was based only on the biosimilar’s ASP (not the original), utilization could jump by 15-20 percentage points. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that switching to a consolidated billing model - where all biosimilars and the reference are paid the same average price - could save Medicare $3.2 billion over ten years. But until that happens, the system favors the status quo.What’s Next for Biosimilar Billing?

CMS is already looking at changes. In February 2023, they asked for public input on whether to eliminate the reference product ASP from the biosimilar add-on calculation. MedPAC, the advisory group to Congress, has recommended adopting a least costly alternative (LCA) model by 2025 - paying all biosimilars the same rate based on the average price of all products in the class. If that happens, providers would have a clear financial reason to choose the cheapest option. Some manufacturers are already preparing: Fresenius Kabi, for example, now includes updated coding guides with every new product launch. But without policy change, adoption will likely plateau around 40-45% by 2027 - far below Europe’s 75%+. The system works - it just doesn’t work well enough to drive real savings.Do biosimilars have the same HCPCS code as the original biologic?

No. Each biosimilar has its own unique HCPCS code - either a J-code (permanent) or Q-code (temporary). The original biologic keeps its own code. For example, Remicade uses J0120, while Inflectra uses Q5101 and Renflexis uses Q5102. This change started in 2018 to ensure each product is billed and paid based on its own price.

Why do I get paid less for a biosimilar even though it costs less?

Because Medicare Part B pays 106% of the Average Selling Price (ASP), but the 6% add-on is calculated using the reference product’s ASP, not the biosimilar’s. So if the original drug costs $2,500 and the biosimilar costs $2,000, you get $150 in add-on for the original but only $120 for the biosimilar - a $30 difference per dose. That makes switching financially unattractive for providers.

What is the JZ modifier and when do I use it?

The JZ modifier is required for infliximab and its biosimilars when the entire vial is used - meaning no drug is discarded. If you have leftover medication (for example, if the vial size is too large for the patient’s dose), you do not use the JZ modifier. This rule took effect on July 1, 2023, and was added to prevent overbilling, but it has increased administrative burden for many clinics.

How often are biosimilar payment rates updated?

Medicare updates biosimilar payment rates quarterly through the Physician Fee Schedule. These updates are based on the most recent Average Selling Price (ASP) data collected by CMS. Providers must check the latest drug pricing files each quarter to avoid claim denials due to outdated codes.

Why are U.S. biosimilar adoption rates lower than in Europe?

Europe uses reference pricing or tendering systems that pay all drugs in a class the same amount - forcing competition on price. In the U.S., the current reimbursement system pays biosimilars based on their own ASP plus 6% of the reference product’s ASP, which reduces the financial incentive to switch. As a result, U.S. biosimilar market share averages 35%, compared to 75-85% in Europe.