Beers Criteria Medication Safety Checker

Enter medications commonly prescribed to older adults to check if they might be inappropriate using the Beers Criteria (2023 version).

Every year, millions of older adults take medications that may no longer be helping them - and might even be hurting them. It’s not that doctors made mistakes. Often, these drugs were prescribed years ago for conditions that have changed or disappeared. Maybe a blood pressure pill was needed after a heart attack, but now the patient’s condition is stable. Maybe a sleeping pill was given for short-term insomnia, but now it’s been taken daily for a decade. This is where deprescribing comes in: the deliberate, careful process of stopping or lowering doses of medicines that are no longer doing more good than harm.

What Is Deprescribing, Really?

Deprescribing isn’t just quitting pills. It’s a clinical decision - one that requires evaluating the patient’s current health, life goals, and risks. The formal definition from researchers at the University of Alberta says it’s about weighing whether the harms of a drug outweigh its benefits, based on the person’s actual function, life expectancy, and personal preferences. That’s not a one-size-fits-all call. A drug that’s safe for a healthy 70-year-old might be dangerous for someone with dementia or kidney disease.

The American Geriatrics Society defines it as the planned and supervised reduction or stopping of medications that could be causing harm or are no longer beneficial. It’s not random. It’s not rushed. It’s done with the same care as when a doctor first prescribes a drug. In fact, experts say deprescribing should mirror prescribing - same level of thought, same documentation, same follow-up.

Why It Matters: The Polypharmacy Problem

In the U.S., about 40% of older adults take five or more medications. One in five take ten or more. That’s not unusual - it’s the norm. But more pills don’t mean better health. Each extra drug adds risk: falls, confusion, stomach bleeding, kidney damage, drug interactions. A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open found that the average older adult with polypharmacy was on 9.74 medications. That’s a lot to manage - and a lot to potentially remove.

Some of these drugs are preventatives: statins for cholesterol, aspirin for heart protection, bone-strengthening pills. But if someone has a life expectancy of less than a year, do those still make sense? If a person can’t walk without help, does a daily calcium tablet really improve their quality of life? These aren’t theoretical questions. They’re daily decisions in clinics across the country.

Deprescribing cuts through the noise. It asks: What’s the goal here? Is it to live longer? Or to live better?

The Five Steps of Safe Deprescribing

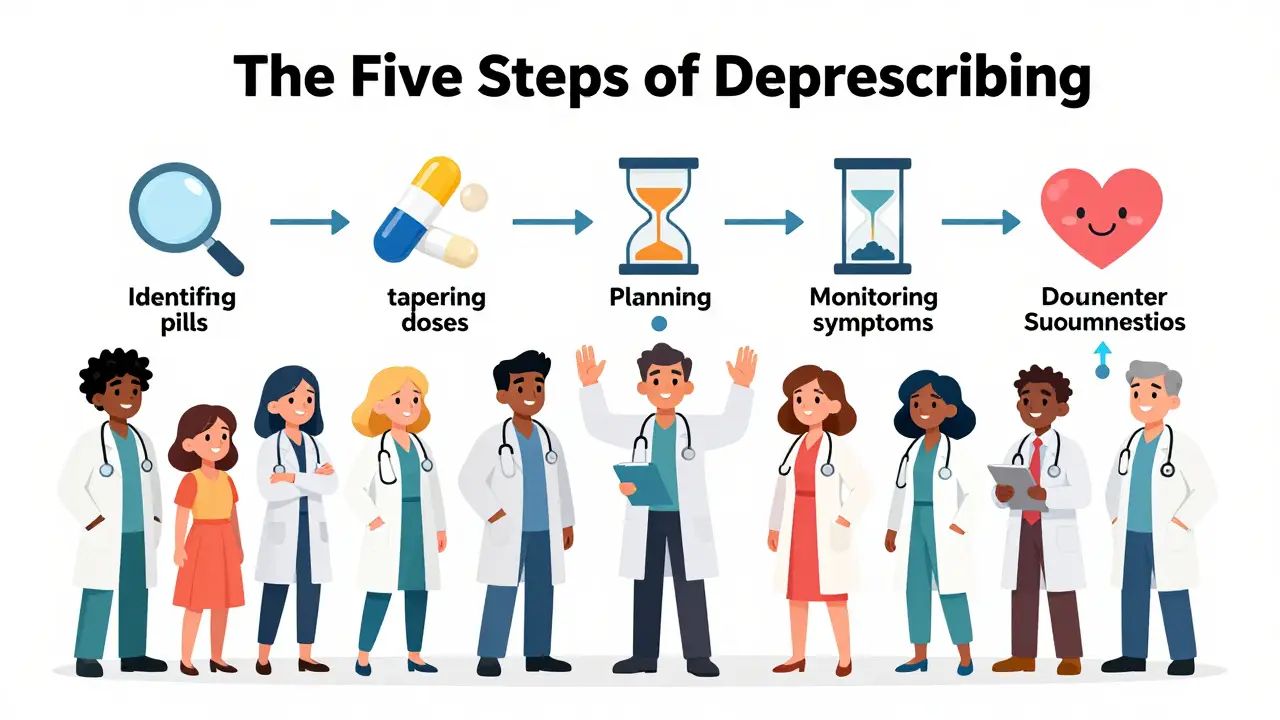

There’s no magic formula, but there is a clear process. Experts agree on five steps:

- Identify which medications might be inappropriate - especially those flagged in the Beers Criteria (updated in 2023) as risky for older adults.

- Determine if the dose can be lowered or stopped. Not all drugs need to go cold turkey. Some can be tapered.

- Plan the reduction. This includes timing, how fast to cut back, and what symptoms to watch for.

- Monitor closely. Withdrawal effects can show up days or weeks later. Blood pressure might rise. Sleep might worsen. Anxiety might creep back. You need to track it.

- Document everything. What was stopped? Why? What happened after? This matters for future care.

One drug at a time. No guessing. No rushing. This isn’t about taking away medicine - it’s about removing what’s no longer serving the patient.

What Does the Research Say About Outcomes?

Early studies focused on how many pills were cut. And yes - deprescribing works. A 2023 meta-analysis showed that for every 7 patients who went through a deprescribing program, one medication was successfully stopped. Sounds small? It’s not. A primary care doctor with 2,000 patients, half of whom are on multiple drugs, could eliminate over 140 unnecessary prescriptions in a year. That’s 140 fewer side effects, 140 fewer pharmacy bills, 140 fewer chances for a dangerous interaction.

But here’s the catch: most studies didn’t measure real outcomes - like falls, hospital visits, or death. They measured pill counts. That’s like judging a cancer screening program by how many mammograms were done, not how many lives were saved.

Some studies, like one from the Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy in 2013, found no difference in hospital admissions or mortality after deprescribing. But those researchers warned: most trials were too short. Patients needed more than 6 months to see real changes. Others, like the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), report stronger evidence: deprescribing leads to fewer falls, better mental clarity, lower hospital use, and improved quality of life.

One of the biggest wins? Reduced confusion. Many older adults on 8+ medications report brain fog. When one or two are removed - often sedatives, anticholinergics, or painkillers - families notice a difference. "Mom’s back to herself," they say.

Who Should Consider Deprescribing?

Not everyone needs it. But certain patients are prime candidates:

- Those with new symptoms that might be drug-related - dizziness, fatigue, confusion, stomach upset.

- People with advanced illness or terminal conditions - where long-term prevention drugs no longer make sense.

- Patients with severe dementia - where drugs for Alzheimer’s, depression, or agitation often cause more harm than good.

- Those on high-risk combinations - like blood thinners plus NSAIDs, or multiple sedatives.

- People on preventive drugs with no clear short-term benefit - statins, aspirin, or osteoporosis meds in someone with limited life expectancy.

It’s not about age. It’s about context. A 75-year-old who hikes, gardens, and travels might keep all their meds. A 78-year-old in a nursing home with advanced dementia? That’s a different story.

What About the Patient’s Voice?

Here’s a truth many clinicians miss: patients want to take fewer pills. A 2019 study from the American Academy of Family Physicians found that older adults would gladly reduce their medication load - if only their doctor brought it up. Most patients assume their prescriptions are permanent. They don’t know they can ask.

That’s why the conversation matters. The best deprescribing happens when doctors say: "I know this pill helped you years ago. But your body’s changed. Let’s see if we can safely lower it - and see how you feel."

Resources like deprescribing.org offer patient-friendly guides. One simple message: "Medications that were good then might not be the best choice now." It’s not about quitting. It’s about adjusting.

Where the System Still Falls Short

Even with strong evidence, deprescribing isn’t routine. Why?

- Time. Doctors have 15-minute visits. Talking about stopping meds takes longer.

- Fear. What if the patient gets worse? What if they blame the doctor?

- Fragmented care. A patient might see a cardiologist, a neurologist, a pain specialist - each prescribing their own drugs. No one’s looking at the whole picture.

- Lack of tools. Electronic health records rarely flag which drugs might be unnecessary. No automated alerts. No easy prompts.

But change is coming. In 2023, the American Academy of Family Physicians began testing point-of-care tools that integrate deprescribing checks into EHRs. In pilot clinics, they cut potentially inappropriate medications by 15%. That’s not a fluke - it’s proof that systems can change.

What’s Next for Deprescribing?

The future is personalized. Researchers are now exploring how genetics affect drug metabolism. For example, some people break down benzodiazepines (sleep aids) slower than others. A simple genetic test could tell a doctor: "This drug will build up in this patient - avoid it." Early trials with proton pump inhibitors (heartburn drugs) are already showing promise.

Also, the focus is shifting from pill counts to real outcomes: falls, hospital stays, cognitive decline, and quality of life. A 2024 study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society stressed the need for deprescribing in patients with multiple doctors - a common problem in older adults. Coordination is key.

And as the population ages - by 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be over 65 - deprescribing won’t be optional. It’ll be essential. The goal isn’t to stop all meds. It’s to make sure every pill in the bottle still has a reason to be there.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Less - It’s About Better

Deprescribing isn’t about taking away. It’s about giving back. Back to clarity. Back to mobility. Back to control. It’s about letting someone live the way they want - not the way their prescription pad says they should.

When done right, it’s one of the most powerful acts of care a clinician can offer: not more treatment - but better treatment.